“Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on. So keep looking until you find it. Don’t settle.”RIP Steve Jobs

Why Peer Advisory Groups Will Be The Next Big Thing

the next big thing, but I believe the time has come for this time-honored practice to take hold as never before. The perfect storm is here. In part it’s because the fundamentals of the peer advisory process itself are aimed squarely at problem solving, visioning, and personal and professional development, but that’s always been the case. The reason for the perfect storm; however, is revealed in the environmental and demographic trends that make the prospects for rapid growth nearly unlimited. First, let’s look at the peer advisory model versus what most companies do today:

the next big thing, but I believe the time has come for this time-honored practice to take hold as never before. The perfect storm is here. In part it’s because the fundamentals of the peer advisory process itself are aimed squarely at problem solving, visioning, and personal and professional development, but that’s always been the case. The reason for the perfect storm; however, is revealed in the environmental and demographic trends that make the prospects for rapid growth nearly unlimited. First, let’s look at the peer advisory model versus what most companies do today:

Peer advisory groups turn the traditional executive development model on its head. The old model, which people have been using for decades now, is designed to train people to be better leaders with the implicit expectation that it will make a difference in how they lead and manage. And that somewhere down the line, the company will actually see the fruits of this investment in its corporate culture and financial performance. The problem is that most executive training is episodic/event-oriented. Someone goes off to training, learns some interesting new concepts, and within a few weeks time, is back to the same old, pre-training behaviors. What’s more, the training and the actual work of the company are often so poorly coordinated that measuring its effectiveness and value are next to impossible.

Peer advisory groups work in exactly the opposite fashion. By having a professional facilitator bring peers together, whether they are colleagues from different areas of a large company or CEOs from different businesses, they can work together as equals with the primary goal of meeting difficult challenges or setting a course for the future. The diversity of the group, coupled with real dialogue, works to create an environment of trust to address larger issues that tend to transcend personal agendas. By setting specific objectives, it’s easy to measure the ROI. Peer groups will ask the hard questions and arrive at their own solutions rather than have to comply with recommendations of trainers or outside consultants. Over time, during this repeated collaborative process of actual problem solving, the participants become better listeners and better leaders. Great results lead to improved leadership behaviors and the cycle continues. It rarely happens the other way around.

So sure, the peer advisory model makes perfect sense, but why will it be the next big thing?

- Large companies are forced to do more with less and are challenged to create alignment within their newly re-organized organizations. To do so in a manner that’s effective and measurable, they will no longer be able to rely on the old “executive development” model of training executives to be better leaders and managers, in the hopes that what they learn in training actually finds its way into meeting the day-to-day needs of the organization. And the continued inability to link training expenditures to producing more competent leaders and better bottom-line results, will result in companies seeking out a more practical way to accomplish both.

- Leaders of smaller companies are finding that the world in which they operate is becoming increasingly complex, especially on the international and technology fronts. The good news is that these challenges are common across industry sectors. As a practical matter (also challenged to do more with less), CEOs and business leaders will likely turn to their peers for guidance instead of paying high-priced consultants or investing in leadership training programs. (And like their larger company colleagues, they’d be wise to do so).

- Today’s younger CEOs are digital natives versus digital immigrants. They grew up with social media and are natural networkers who are much more inclined than their predecessors to engage their peers for advice and counsel.

- There’s been a fundamental shift in management education aimed at leveraging the experience of the increasing number of adult learners in the classroom, in both traditional and online education environments. The practice of andragogy, or learning centered environments geared to adults, is becoming increasingly more popular, replacing pedagogy (a teaching centered/lecture-oriented approach) that relies more on the knowledge of the instructor than in the inherent experience and collective insights of the group. It’s only a matter of time before it finds its way more prominently into private enterprise.

- As I pointed out in my last post, there are many similarities between learning teams and peer advisory groups. Adult learners who’ve grown accustomed to working in peer groups in school, will seek to continue the practice in the workplace in greater numbers. Peer groups at work will replace the learning teams they left behind.

Professionally facilitated peer groups simply make too much sense in today’s world not to catch fire – and soon! Now I understand if you’re skeptical about a Vistage employee making the case for why professionally facilitated peer advisory groups is the next big thing. Since it is what we do, I might be wary as well. So I ask you to consider the argument on its merits, offer your comments (positive or negative), and understand that no self respecting advocate of peer advisory groups would ever presume to write such a post without consulting his peers. This is not my opinion alone. Thanks to my colleagues at Vistage and Seton Hall University for your contributions to this piece!

The Heresy of Netflix via @forbes

Robert Passikoff, Contributor

Convention has it that the one thing you must not discuss with the father of the girl you’re dating is politics; with the mother, religion, but even convention has its moments.

We dance around religion and politics because you will not find more passionate, easily ignitable people on earth than those who hold a belief deeply. Netflix co-founder and chief executive Reed Hastings is finding this out, to his grief and financial loss, as his actions cause brand believers to lose the faith. After springing some spectacular pricing “options” on customers, this past Sunday Hastings made the widely panned decision to split Netflix in two, leaving Netflix proper to handle the Internet-streaming service and assigning the new company, Qwikster, the DVD-by-mail business. Sure, it’s a questionable business decision to begin with, but the true heresy lies not in dividing the company, but in breaking down the lines of communication between the Netflix brand and the brand’s many faithful disciples. According to the Wall Street Journal, 17,000 former Netflix believers fired back in the Netflix blog’s comments section, faith obviously shaken to the foundation at this unexpected and largely unexplained change. Netflix users are feeling unheard and uncared for, their thoughts and opinions bounding back on them like so many unanswered prayers. This has also showed up in Brand Keys Loyalty numbers. At the beginning of the year, Netflix had a comparable brand strength – an ability to delight – of 99%. Not bad, huh? After the change in pricing policies that moved down to 93%. As of today? 87%. Any beloved brand has a differentiating feature, a hook that gives brand fanatics something to hang their hats on, and Netflix’s was customer care and responsiveness. This breach of faith is potentially damning to Netflix. Because the world is full of things for consumers to believe in, and in the battle for consumer devotion, no brand is sacred.

"Most people are not smelling their wine enough!" No, seriously...

Windows 8 "Upgrades" the Blue Screen of Death via @mashable

Six years ago, I tossed my Dell Laptop out the window, went to the Apple store and bought my first MacBook Pro. Now, another MacBook, an iMac, two iPads and four iPhones later... I can barely remember what the Blue Screen of Death looks like. It strikes me as funny that Microsoft chose to "upgrade" it!

by

If you are or ever were a Windows user, you’re likely familiar with the Blue Screen of Death (BSoD). The bug check screen, with its lines of error codes, has been part of Windows since version 1.0. It has represented the crashing of computers — and the frustration of users — for decades.

The BSoD was never intended to be user friendly, though. It was made for engineers who wanted to figure out why a PC crashed. For the rest of the world, it signifies the downside of owning a Windows device. The iconic Stop Error screen is getting a facelift with Windows 8. The redesigned OS also includes speed and stability improvements, a Metro interface optimized for touchscreens and an app store. We’re fans of the new error screen — it’s much clearer and more user-friendly — though we hope there’ll be fewer chances to see it. But we want to hear your thoughts. Do you like the new Blue Screen of Death? Let us know in the comments. Image courtesy of Mobility Digest

Privacy Advocates Criticize Icon Program, Call For New Regs via @mediapost

by Wendy Davis

A coalition of advocacy groups in the U.S. and Europe are calling on government officials to reject the ad industry's self-regulatory privacy program.

"Consumers in both the US and EU are offered limited options, based on principles crafted by the digital marketing industry and 'enforced' by groups that do not represent consumers or governments and that are completely lacking in any independence from the industry they are intended to monitor," the groups say in a letter sent Thursday to Federal Trade Commission consumer protection head David Vladeck, European privacy official Jacob Kohnstamm and other regulators. U.S. groups signing the letter include Consumers Union, the Electronic Privacy Information Center and the Center for Digital Democracy. The self-regulatory program requires that ad companies engaged in behavioral targeting notify consumers about the technique via an icon and to allow them to opt out of receiving targeted ads. The rules allow ad companies to continue to collect information about users who opt out. The Better Business Bureau's National Advertising Review Council is enforcing the program, created by the umbrella group Digital Advertising Alliance. The privacy advocates argue that the icon program falls short because "industry research" shows that "very few users ever click on it, let alone decide to opt-out." The advocates also say the icon doesn't sufficiently inform people about the "wide range of data collection that they routinely face." The privacy coalition, dubbed TransAtlantic Consumer Dialogue, is urging officials in the U.S. and EU to undertake a number of new steps, including enacting regulations to "address new threats to consumer privacy from the growth of real-time tracking and sales of information about individuals' online activities on ad exchanges and other similar platforms." Stuart Ingis, counsel to the DAA, disputes the groups' criticisms. He says that the Better Business Bureau has "100% independence" from industry. "The Better Business Bureau has done effective self-regulation independent of the industry for years," Ingis says. ![]()

"A Lifespan is a Billion Heartbeats"...

... and Nine Other Things Everyone Should Know About Time

A lifespan is a billion heartbeats. Complex organisms die. Sad though it is in individual cases, it’s a necessary part of the bigger picture; life pushes out the old to make way for the new. Remarkably, there exist simple scaling laws relating animal metabolism to body mass. Larger animals live longer; but they also metabolize slower, as manifested in slower heart rates. These effects cancel out, so that animals from shrews to blue whales have lifespans with just about equal number of heartbeats — about one and a half billion, if you simply must be precise. In that very real sense, all animal species experience “the same amount of time.”

Time” is the most used noun in the English language, yet it remains a mystery. We’ve just completed an amazingly intense and rewarding multidisciplinary conference on the nature of time, and my brain is swimming with ideas and new questions. Rather than trying a summary (the talks will be online soon), here’s my stab at a top ten list partly inspired by our discussions: the things everyone should know about time.

1. Time exists. Might as well get this common question out of the way. Of course time exists — otherwise how would we set our alarm clocks? Time organizes the universe into an ordered series of moments, and thank goodness; what a mess it would be if reality were complete different from moment to moment. The real question is whether or not time is fundamental, or perhaps emergent. We used to think that “temperature” was a basic category of nature, but now we know it emerges from the motion of atoms. When it comes to whether time is fundamental, the answer is: nobody knows. My bet is “yes,” but we’ll need to understand quantum gravity much better before we can say for sure.

2. The past and future are equally real. This isn’t completely accepted, but it should be. Intuitively we think that the “now” is real, while the past is fixed and in the books, and the future hasn’t yet occurred. But physics teaches us something remarkable: every event in the past and future is implicit in the current moment. This is hard to see in our everyday lives, since we’re nowhere close to knowing everything about the universe at any moment, nor will we ever be — but the equations don’t lie. As Einstein put it, “It appears therefore more natural to think of physical reality as a four dimensional existence, instead of, as hitherto, the evolution of a three dimensional existence.”

3. Everyone experiences time differently. This is true at the level of both physics and biology. Within physics, we used to have Sir Isaac Newton’s view of time, which was universal and shared by everyone. But then Einstein came along and explained that how much time elapses for a person depends on how they travel through space (especially near the speed of light) as well as the gravitational field (especially if its near a black hole). From a biological or psychological perspective, the time measured by atomic clocks isn’t as important as the time measured by our internal rhythms and the accumulation of memories. That happens differently depending on who we are and what we are experiencing; there’s a real sense in which time moves more quickly when we’re older.

4. You live in the past. About 80 milliseconds in the past, to be precise. Use one hand to touch your nose, and the other to touch one of your feet, at exactly the same time. You will experience them as simultaneous acts. But that’s mysterious — clearly it takes more time for the signal to travel up your nerves from your feet to your brain than from your nose. The reconciliation is simple: our conscious experience takes time to assemble, and your brain waits for all the relevant input before it experiences the “now.” Experiments have shown that the lag between things happening and us experiencing them is about 80 milliseconds. (Via conference participant David Eagleman.)

5. Your memory isn’t as good as you think. When you remember an event in the past, your brain uses a very similar technique to imagining the future. The process is less like “replaying a video” than “putting on a play from a script.” If the script is wrong for whatever reason, you can have a false memory that is just as vivid as a true one. Eyewitness testimony, it turns out, is one of the least reliable forms of evidence allowed into courtrooms. (Via conference participants Kathleen McDermott and Henry Roediger.)

6. Consciousness depends on manipulating time. Many cognitive abilities are important for consciousness, and we don’t yet have a complete picture. But it’s clear that the ability to manipulate time and possibility is a crucial feature. In contrast to aquatic life, land-based animals, whose vision-based sensory field extends for hundreds of meters, have time to contemplate a variety of actions and pick the best one. The origin of grammar allowed us to talk about such hypothetical futures with each other. Consciousness wouldn’t be possible without the ability to imagine other times. (Via conference participantMalcolm MacIver.)

7. Disorder increases as time passes. At the heart of every difference between the past and future — memory, aging, causality, free will — is the fact that the universe is evolving from order to disorder. Entropy is increasing, as we physicists say. There are more ways to be disorderly (high entropy) than orderly (low entropy), so the increase of entropy seems natural. But to explain the lower entropy of past times we need to go all the way back to the Big Bang. We still haven’t answered the hard questions: why was entropy low near the Big Bang, and how does increasing entropy account for memory and causality and all the rest? (We heard great talks by David Albert and David Wallace, among others.)

8. Complexity comes and goes. Other than creationists, most people have no trouble appreciating the difference between “orderly” (low entropy) and “complex.” Entropy increases, but complexity is ephemeral; it increases and decreases in complex ways, unsurprisingly enough. Part of the “job” of complex structures is to increase entropy, e.g. in the origin of life. But we’re far from having a complete understanding of this crucial phenomenon. (Talks by Mike Russell, Richard Lenski, Raissa D’Souza.)

9. Aging can be reversed. We all grow old, part of the general trend toward growing disorder. But it’s only the universe as a whole that must increase in entropy, not every individual piece of it. (Otherwise it would be impossible to build a refrigerator.) Reversing the arrow of time for living organisms is a technological challenge, not a physical impossibility. And we’re making progress on a few fronts: stem cells, yeast, and even (with caveats) mice and human muscle tissue. As one biologist told me: “You and I won’t live forever. But as for our grandkids, I’m not placing any bets.”

(Amazing talk by Geoffrey West.)

Four Ways to Kill a Good Idea

Someone is out to shoot down your best ideas. Do you know how to defend yourself? In their new book, Buy-IN: Saving Your Good Idea from Getting Shot Down, HBS professor emeritus John P. Kotter and University of British Columbia professor Lorne A. Whitehead teach how to get past the "confounding questions, inane comments, and verbal bullets." This excerpt looks at attack strategies used by naysayers: fear mongering, delay, confusion, ridicule. Book excerpt from Buy-IN: Saving Your Good Idea from Getting Shot Down By John P. Kotter and Lorne A. Whitehead This kind of attack strategy is aimed at raising anxieties so that a thoughtful examination of a proposal is very difficult if not impossible. People begin to worry that implementing a genuinely good plan, pursuing a great idea, or making a needed vision a reality might be filled with frightening risks—even though that is not really the case. There are all sorts of ways to create fear. You have seen a half dozen in the library story. The trick is to start with an undeniable fact and then to spin a tale that ends with consequences that are genuinely frightening or that just push the anxiety buttons we all have. The logic that goes from the fact to the dreadful consequence will be wrong, maybe even silly. A story that reminds us of scary events in the past may not be a fair analog, but it can be effective in bringing up unpleasant memories. Pushing anxiety buttons is manipulative in the worse sense of the word. But it can be an effective tactic. Once aroused, anxieties do not necessarily disappear when a person is confronted with an analytically sound rebuttal. If humans were only logical creatures, this would not be a problem. But we are not. Far from it…. We see this problem all the time when people are trying to help an organization deal with a changing environment or to exploit a new and significant opportunity. In one typical case, a sizable change was needed inside a firm. With effort, some people did develop an innovative vision of what changes would be needed and a smart strategy of how to make those changes. Then, in trying to explain this to others and achieve sufficient buy-in, the initiators ran into someone who noted (correctly) that the last time they tried a big change (in their case, the "customer centric" initiative), they were unsuccessful, and some of the consequences (impossible workloads for a while, a few good people's careers derailed) were very unpleasant. Anxiety began to grow as others used the wordscustomer centric again and again. No one made a perfectly logical case for how the historical and current situations were comparable. But that didn't matter. An undercurrent of fear became a riptide, and the new change vision and strategies never gained sufficient buy-in to make the change effort successful. Even if most people see an anxiety-creating attack for what it is, if those who don't see the fallacy of the logic constitute more than a small percentage of a group, you might still have a serious problem that must be handled with care. Even a single smart or credible person, if made fearful, can be tipped not only toward opposing a proposal, but also toward using attack tactics that tip still more people. Anxiety then builds like an infection.… People use fear-mongering strategies with voices that are beastly or, more often, ones that are oh-so-innocently calm. People can know very clearly what they are doing and why, or they can be completely oblivious to the way they're acting. One doesn't have to be an unethical or a self-serving person to use a strategy that raises anxieties and kills off a good idea. And that fact has huge implications regarding what you must do to deal effectively with fear mongering and all the other attack strategies (more on that soon). There are questions and concerns that can kill a good proposal simply by creating a deadly delay. They so slow the communication and discussion of a plan that sufficient buy-in cannot be achieved before a critical cut-off time or date. They make what may seem like a logical suggestion but which, if accepted, will make the project miss its window of opportunity. Death-by-delay tactics can force so many meetings or so many straw polls that momentum is lost, or another idea, not nearly as good, gains a foothold…. Death by delay can be a very powerful strategy because it's so easy to deploy. A case is made that sounds so reasonable, where we should wait (just a bit) until some other project is done, or we should send this back into committee (just to straighten up a few points), or (just) put off the activity until the next budget cycle. With a delay strategy, attention can be diverted to some legitimate, pressing issue, the sort of which always exists. There is the sudden budget shortfall, the unexpected competitor announcement, the dangerous new bill put before the legislature, the growing problem here, the escalating conflict there. These can require immediate attention, but rarely 100 percent of people's attention. With death by delay, the point is to focus people 100 percent on the crisis so that a good idea is forgotten or crucial communication is lost. Growing momentum toward buy-in then slows to the point that it can never be regained. We recently saw a version of this, which you might call the "we have too much on our plate right now" argument. It is possible to have too many projects, where clearly any recommended action should be cutting back, not adding more. But in this case, the proposal was for a very innovative automotive parts product, and no one could have logically defended the superior worth of all the other projects in the works. But those who were running some of the current programs, and receiving considerable resources for doing so, correctly saw the new proposal as a threat, which they successfully killed with a too-much-on-our-plate-right-now bullet. Because it is so easy to use, death by delay is a weapon available to nearly anyone, which makes it particularly dangerous. Yet, as with the other three attack strategies, the many little bombs it creates can all be defused. Some idea-killing questions and concerns muddle the conversation with irrelevant facts, convoluted logic, or so many alternatives that it is impossible to have the clear and intelligent dialog that builds buy-in. Heidi Agenda hit Hank with "what about, what about, what about?" With that attack, it's easy for a conversation to slide into endless side discussions about this and that, and that and this, and don't forget about . . . Eventually, people conclude that the idea has not been well thought out. Or they feel stupid because they cannot follow the conversation (which tends to create anger, which can flow back toward the proposal or the proposer). Or they get that head-about-to-burst feeling, which they relieve by setting aside the proposal or plan. Some individuals can be astonishingly clever at drawing you into a discussion that is so complex that a reasonable person simply gives up and walks away.… A confused person might still vote yes, but only to stop the conversation and with no commitment toward making the idea become a reality. A complex topic is not needed for a confusion strategy to work. Even the simplest of plans can be pulled into a forest of complexity where nearly anyone can become lost. Statistics can be powerful weapons, used not to clarify but to bewilder. "You are trying to solve a problem that doesn't exist. Just look at this [twenty-two-page] spreadsheet. I think if we study it closely . . ." Complex stories, about which most people do not know the details, can be lethal. "What about the Teledix project [which no one has ever heard of] and the competitive strategy we have for the TX line of products [a strategy that half the people in the room know nothing of]? I worry that the interaction of Teledix, TX, and this proposal will hurt third-quarter income, at least in Asia, which would be very bad. Don't you think so?"… We recently watched a presentation communicated in PowerPoint slides, all sixty-eight of them, and many in impossible-to-read small print.… The slide deck "demonstrated" why a proposal to allocate many more resources to building a firm's business in Europe went too far. The document is incomprehensible (we have yet to find anyone in that firm who can explain it clearly), but it has successfully undermined support for a plan that is probably a very good one. Some verbal bullets don't shoot directly at the idea but at the people behind the idea. The proposers may be made to look silly. Questions may be raised about competence. Slyly or directly, questions can be raised about character. Strong buy-in is rarely achieved if an audience feels uneasy with those presenting a proposal.… Without even saying the words, a question is raised about whether you are smart enough to have done careful homework on a problem, or visionary enough to see better alternatives…. Questions and concerns based on a strategy of ridicule and character assassination can be served with a dramatic flourish of indignation, but more often are presented with a light hand. There is a sense that the attacker feels awkward even bringing up a subject, but he nevertheless feels it is his duty to ask whether George's dinners with his admin assistant might . . . No, no, that wasn't fair. Forget I said that. The ridicule strategy is used less than the others, probably because it can snap back at the attacker. But when this strategy works, there can be collateral damage. Not only is a good idea wounded, and a person's reputation unfairly tarnished, but all the additional sensible ideas from the proposer might have less credibility, at least until the memory of the attack fades. Fear mongering

Delay

Confusion

Ridicule (or character assassination)

The Growth of Social Media

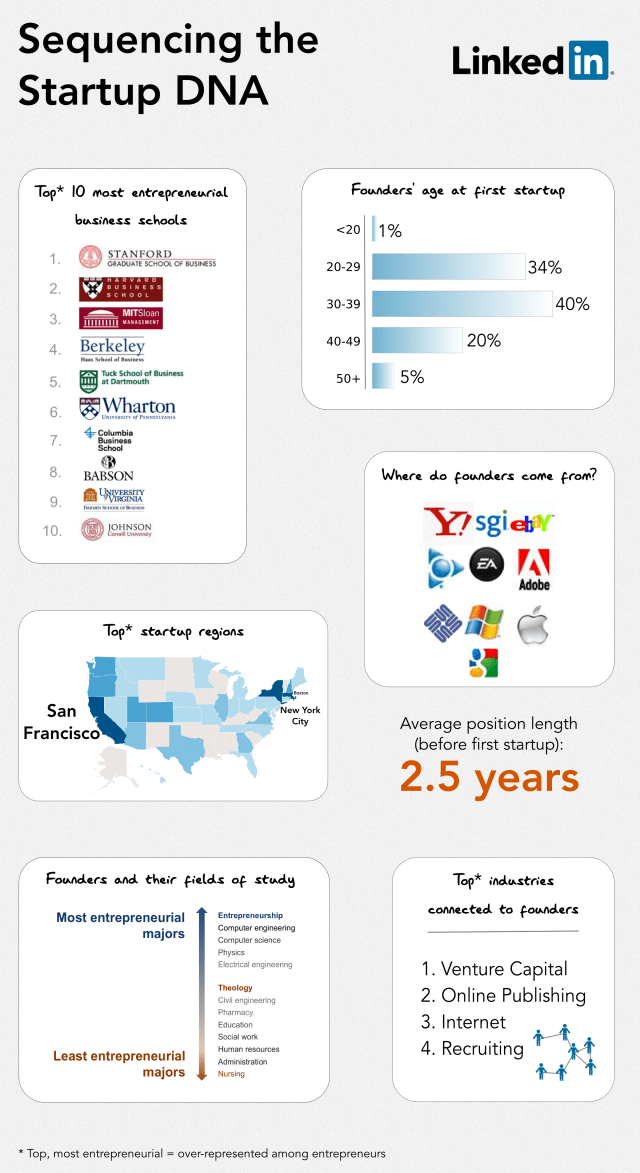

LinkedIn Takes A Deep Data Dive On Startup Founder Profiles

Groupon's MySpace Moment?

via @forbes

MySpace Moment, sooner or later, is going to enter the Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary alongside crowdsourcing, bromance and cougars. It is a fact that once seemingly invincible brands can inexplicably decline in popularity so let’s give this depressing phenomena a name so we can say, oh, I don’t know, Groupon may be nearing a MySpace Moment.

Which it may be.

Something is amiss: The Securities and Exchange Commission frowned upon – and legions of accountants mocked – its Adjusted Consolidated Segment Operating Income metric in its first filing. It inflated the company’s worth by ignoring marketing costs. Groupon subsequently amended its filling.

It posted a net loss in the second quarter (although much of that was related to the hiring of more than 1,000 employees).

Now Experian Hitwise is reporting a significant drop-off in Groupon traffic this summer, nearly 50% since its peak in the second week of June 2011 compared to last week.

During the same time, Living Social has achieved 27% growth in visits to its site.

These are just two data points, of course, and they ignore the formidable assets that Groupon does have – namely its email mailing list, which CEO Andrew Mason pointed out in a recent internal memo to employees (the only way the company has to defend itself now that it is in a quiet period) and head start in this market and name recognition.

It has also been pushing into real time mobile offerings with Groupon Now.

And it’s not that other sites don’t dip in traffic every now and then – or even fail to turn lagging initiatives around. Remember Google’s social media efforts pre-Google+?

Or eBay’s diversification away from the auction model

Are Daily Deals Sustainable?

In fact eBay is a good company to point to right now. Ten-fifteen years ago, it was auction-everything thanks to eBay’s wild popularity at the time. To be sure, there is still a market for that business style but as eBay itself has shown with its emphasis on fixed-pricing, it is better to diversity into other categories as well.

So may it be with the daily deal model. Doubts are growing whether its current form is sustainable – by that I mean, will there be enough consumers to fuel the 400 plus daily deal offerings in the long run? Or merchants, for that matter? One point made by Experian Hitwise that does not bode well for Groupon or the model is that overall visits to a custom category of Daily Deal & Aggregator sites were down 25% for the same time period. Also, it noted PriceGrabber released results from its Local Deals Survey in June, stating that 44% of respondents said they use or search daily deal Websites. “However, 52% expressed feeling overwhelmed by the number of bargain-boasting emails they receive on a daily basis.”

NBA's Problem Is Not Player Salaries

via @BISportsPage

The NBA claims that 22 teams lost money last season, with a total loss of $370 million. And to fix the problem, the league wants to rein in player salaries. But a closer look at the numbers suggest the problem does not lie with the players' paychecks.

On the surface, this should be obvious. Since the NBA and the players ratified the most recent Collective Bargaining Agreement prior to the 2005-06 season, player salaries have been fixed at 57 percent of league revenue. And if we adjust player salaries for inflation (via Nate Silver), salaries are only up 5.4 percent since the beginning of the previous CBA that the NBA owners happily agreed to. In that same time period, revenue was up 5.3 percent. However, league income in the last five years is down 31.1 percent. Why? Because spending by the owners on everything else besides player salaries is up 12.7 percent, outpacing league revenue growth. Still, in the end, according to the data from Forbes.com, the league is still making money. It is making less money, and certainly the owners want to make more. But the idea that the league is losing money may not be accurate. And even if they are losing money, they only have their own spending habits to blame.

|

Adopt a Duck. Win a Car. Save a Life.

Join our team! Manu Ginobili and I have teamed up to rasie money for Haven for Hope here in San Antonio. Adopt a Duck for $5!

How to Taste Wine

I found this useful...

How to Taste Wine

Edited byKathy Howe and 37 others

Whenever you come across fertile wine country, wine tasting is often one of the most rewarding excursions available. If you long to walk through the vineyards and admire the grapevines and picturesque backdrop, wine glass in hand, you must first learn to appreciate the subtle beauty of wine.

Steps

1

Look at the wine, especially around the edges. Tilting the glass a bit can make it easier to see the way the color changes from the center to the edges. Holding the glass in front of a white background, such as a napkin, tablecloth, or sheet of paper, is another good way to make out the wine's true color. Look for the color of the wine and the clarity. Intensity, depth or saturation of color are not necessarily linear with quality. White wines become darker as they age while time causes red wines to lose their color turning more brownish, often with a small amount of harmless, dark red sediment in the bottom of the bottle or glass. This is also a good time to catch a preliminary sniff of the wine so you can compare its fragrance after swirling.

This will also allow you to check for any off odors that might indicate spoiled (corked) wine.

2

Swirl the wine in your glass. This is to increase the surface area of the wine by spreading it over the inside of the glass allowing them to escape from solution and reach your nose. It also allows some oxygen into the wine, which will help its aromas open up.

3

Note the wine's viscosity - how slowly it runs back down the side of the glass - while you're swirling. More viscous wines are said to have "legs," and are likely to be more alcoholic. Outside of looking pretty, this has no relation to a wine's quality but may indicate a more full bodied wine.

4

Sniff the wine. Initially you should hold the glass a few inches from your nose. Then let your nose go into the glass. What do you smell?

5

Take a sip of wine, but do not swallow yet. Roll the wine around in your mouth exposing it to all of your taste buds. You will only be able to detect sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami (think: meaty or savory). Pay attention to the texture and other tactile sensations such as an apparent sense of weight or body.

6

Aspirate through the wine: With your lips pursed as if you were to whistle, draw some air into your mouth and exhale through your nose. This liberates the aromas for the wine and allows them to reach your nose where they can be detected. The nose is the only place where you can detect a wine's aromas. However, the enzymes and other compounds in your mouth and saliva alter some of a wine's aromatic compounds. By aspirating through the wine, you are looking for any new aromas liberated by the wine's interaction with the environment of your mouth.

7

Take another sip of the wine, but this time (especially if you are drinking a red wine) introduce air with it. In other words, slurp the wine (without making a loud slurping noise, of course). Note the subtle differences in flavor and texture.

8

Note the aftertaste when you swallow. How long does the finish last? Do you like the taste?

9

Write down what you experienced. You can use whatever terminology you feel comfortable with. The most important thing to write down is your impression of the wine and how much you liked it. Many wineries provide booklets and pens so that you can take your own tasting notes. This will force you to pay attention to the subtleties of the wine. Also, you will have a record of what the wine tastes like so that you can pair it with meals or with yourmood.

Wines have four basic components: taste, tannins, alcohol and acidity. Some wines also have sweetness - but the latter is only appropriate in dessert wines. A good wine will have a good balance of all four characteristics. Aging will soften tannins (see Tips for a more detailed description). Acidity will soften throughout the life of a wine as it undergoes chemical changes which include the break down of acids. Fruit will rise and then fall throughout the life of a wine. Alcohol will stay the same. All of these factors contribute to knowing when to drink/decant a wine.

Here are some commonly found tastes for each of the most common varieties (bear in mind that growing region, harvesting decisions and other production decisions have a great impact on a wine's flavor character):

Cabernet - black currant, cherry other, black fruits, green spices

Merlot - plum, red and black fruits, green spices, floral

Zinfandel - black fruits (often jammy), black spices - often called "briary"

Syrah (aka Shiraz, depending on vineyard location) - black fruits, black spices - especially white and black pepper

Pinot Noir - red fruits, floral, herbs

Chardonnay - cool climate: tropical fruit, citrus fruit in slightly warmer climes and melon in warm regions. With increasing proportion of malolactic fermentation, Chardonnay loses green apple and takes on creamy notes, Apple, pear, peach,apricot

Sauvignon Blanc - Grapefruit, white gooseberry, lime, melon

Malolactic fermentation (the natural or artificial introduction of a specific bacteria) will cause white wines to taste creamy or buttery

Aging in oak will cause wines to take on a vanilla or nutty flavor.

Other common taste descriptors are minerality, earthiness and asparagus.

10

Match the glassware to the wine. Stemware/drinkware comes in a variety of shapes and sizes. The more experienced wine drinkers and connoisseurs often enjoy wines out of stemware or bulbs that are tailor-made for a specific varietal. When starting out, there is a basic rule of thumb; larger glasses for reds, and smaller glasses for whites. Austrian glassware company Riedel is the gold standard of drinkware when it comes to wine, but for the beginner, less expensive stemware will do.

11

Try pairing wines with unusual ingredients and note the how it enhances or diminishes the flavors of the wine. With red wines try different cheeses, good quality chocolate and berries. With white wines you can try apples, pears and citrus fruits. Pairing wine with food is more complicated than "red with beef and white with fish." Feel free to drink whichever wine you want with whatever food you want, but remember a perfect pairing is a highly enjoyable experience.

12

Ultimately, a wine should complement the food and cleanse the palate. So big, jammy, sweet wines will not do as well as ones with a more composed bouquet or aromas and high acidity.

Are You a Role Model?

It's impressive that Warren Buffett has earned billions of dollars. It's even more impressive that he's the only billionaire with the good grace and social conscience to state the obvious: people like him ought to be paying far higher taxes than they do, especially in these debt-riddled times.

But what's most impressive about Warren Buffett is that he recognizes his wealth and success are not simply a function of his skills. As he acknowledges, he also had the incredible good fortune to be born into money and privilege, which provided him with endless support, social capital and opportunity.

"If you stick me down in the middle of Bangladesh or Peru, "Buffett says, "you'll find out how much this talent is going to produce in the wrong kind of soil."

Countless others who've built tremendous fortunes have also benefited from the same kind of luck, yet believe, either out of grandiosity or obliviousness, that they've done so solely by their own wits.

Show me a person who has built wealth, without trampling others to get it, and I will show you someone who has benefited deeply from good fortune and from countless mentors and teachers along the way.

It takes a village.

Let's also blow up, once and for all, the myth that there's something admirable about earning a great deal of money.

Let's save our admiration for people whose lives are about serving a greater good, and our greatest admiration for those who are willing to make sacrifices to do so.

The vast majority of the wealthiest people I've met are far more about building value for themselves than they are about creating value for anyone or anything beyond themselves.

We reward and admire the wrong people for the wrong reasons.

Is there any head of a hedge fund who has stood up publicly, the way Warren Buffett now has, and said, "It's absurd that I should be paying lower taxes than someone who earns $30,000 a year"?Is there any CEO of a Fortune 500 company who has told his board of directors, "It's outrageous to pay me millions of dollars a year at a time when we're laying off employees. Pay me more reasonably, and let's spend the rest of the money keeping more of our people employed"?

I admire the administrators, principals and teachers at the KIPP charter schools who work 14-hour days, 11 months a year, to give disadvantaged inner city kids the chance they deserve.

I admire anyone who chooses teaching as a profession, especially when they could make far more money in another profession.

I admire the intensive care nurses I met several years ago at the Cleveland Clinic, who get treated as second-class citizens by most of the surgeons, but still put in 12-hour shifts, often without the opportunity to sit down, or eat, or even go to the bathroom. They do so because they're devoted to saving lives.

I admire a politician such as Cory Booker, who grew up in an upper middle class home, attended Stanford and Yale law school, and could easily have become a corporate lawyer or an investment banker. Instead, he chose to settle in a modest apartment in Newark, New Jersey, and try to turn around one of the toughest cities in America, by becoming its mayor.

It's great that Warren Buffett and Bill Gates launched the "Giving Pledge" to which they and other billionaires have committed to give away the majority of their wealth during their lifetimes.

Still, let's not confuse that with sacrifice. None of those who've made the Giving Pledge will live any less well as a result of giving away half their fortunes, nor will their children, or their children's children.

Deep generosity — generosity that requires personal sacrifice — is something else altogether. It's the $15-an-hour worker who puts $10 in the collection plate every week, or lends money to a friend in even greater need, and therefore has less money available to put food on the table for his family.

"To whom much is given," the parable goes in Luke 12:35, "of him much will be required." Fairness is the sine qua non of any sustainable society.

What we need more of — especially from billionaires, but also from any of us who have more than we need — is the sense of responsibility that Warren Buffett has now demonstrated.

What we need most, however, are more role models for the sort of deep generosity that involves true sacrifice.

Tony Schwartz is the president and CEO of The Energy Project and the author of Be Excellent at Anything. Become a fan of The Energy Project on Facebook and connect with Tony at Twitter.com/TonySchwartz and Twitter.com/Energy_Project.

TONY SCHWARTZ

How to Use the Power of Silence to Be Heard

The popular idiom says the squeaky wheel gets the grease, but if you really want to increase the potency of your voice, silence can be a powerful tool. Entrepreneur Daniel Tenner explains.

From my father's blog on wisdom: If you have a gift with words, learn to keep your mouth shut; when you speak, punctuate with pause; and when you have nothing to say, say nothing. (...) Your silence passes many messages; one is that you are somebody, not nobody, a person able to face a crowd and to wait. This is an almost biological power of the big secure animal looking at harmless ones. People understand or better said they feel. After this, you have a better chance to be listened to. Silence has tremendous applications in the business world too, of course. For me, the "aha" moment about silence came when I was working on my first startup, while still working full time as a consultant in Accenture. I was sleeping about 4 hours a night for 9 months, and so I was constantly tired. At the time I was managing a small team of people who often did not get along. So, every once in a while, I would have to set up meetings with me and two other people to resolve their conflict and keep the project moving forward. Because I was so tired, I spent most of my time in the meetings quiet, minimising even physical movement. I would sit and listen and let the meeting go its way until I came to a moment where I felt that if I did not say something - the right thing - just at that moment, with just the right body language to support it, things would go wrong sooner or later and I would have to pay with even more tiresome activity. I wasn't scared of being "found out" for doing the bare minimum in meetings. I was starting my first business and I believed I would be out of the corporate world soon (and I was). But I noticed something very strange. Because I talked so rarely, every time I spoke, people stopped talking and took the time to listen to me. By doing much, much less, I had somehow given the little that I did do a lot more weight. Since then, I've used silence in many other contexts. It can be a very useful tool for sales, for example: when you're trying to close a sale, at one point you need to state your pitch, with the price, and then just shut up. If you keep talking, you will only distract the customer from evaluating the pitch and coming to a decision. In person-to-person conversations, few people can stand a prolonged silence, particularly when it follows a certain kind of statement. "I don't know what I can do to solve X," followed by silence, will often pull suggestions for solving X out of someone who would not have volunteered them for "how should I solve X?" Learn to use silence. It is a powerful tool in many contexts.

Latest in Web Tracking: Stealthy 'Supercookies' via @wsj

By JULIA ANGWIN

Major websites such as MSN.com and Hulu.com have been tracking people's online activities using powerful new methods that are almost impossible for computer users to detect, new research shows.

What 'History Stealing' Is

The new techniques, which are legal, reach beyond the traditional "cookie," a small file that websites routinely install on users' computers to help track their activities online. Hulu and MSN were installing files known as "supercookies," which are capable of re-creating users' profiles after people deleted regular cookies, according to researchers at Stanford University and University of California at Berkeley.

Websites and advertisers have faced strong criticism for collecting and selling personal data about computer users without their knowledge, and a half-dozen privacy bills have been introduced on Capitol Hill this year.

Many of the companies found to be using the new techniques say the tracking was inadvertent and they stopped it after being contacted by the researchers.

Mike Hintze, associate general counsel at MSN parent company Microsoft Corp., said that when the supercookie "was brought to our attention, we were alarmed. It was inconsistent with our intent and our policy." He said the company removed the computer code, which had been created by Microsoft.

Hulu posted a statement online saying it "acted immediately to investigate and address" the issues identified by researchers. It declined to comment further.

The spread of advanced tracking techniques shows how quickly data-tracking companies are adapting their techniques. When The Wall Street Journal examined tracking tools on major websites last year, most of these more aggressive techniques were not in wide use.

But as consumers become savvier about protecting their privacy online, the new techniques appear to be gaining ground.

Stanford researcher Jonathan Mayer, a Stanford Ph.D. candidate, identified what is known as a "history stealing" tracking service on Flixster.com, a social-networking service for movie fans recently acquired by Time Warner Inc., and on Charter CommunicationsInc.'s Charter.net.

Such tracking peers into people's Web-browsing histories to see if they previously had visited any of more than 1,500 websites, including ones dealing with fertility problems, menopause and credit repair, the researchers said. History stealing has been identified on other sites in recent years, but rarely at that scale.

Mr. Mayer determined that the history stealing on those two sites was being done by Epic Media Group, a New York digital-marketing company. Charter and Flixster said they didn't have a direct relationship with Epic, but as is common in online advertising, Epic's tracking service was installed by advertisers.

Don Mathis, chief executive of Epic, says his company was inadvertently using the technology and no longer uses it. He said the information was used only to verify the accuracy of data that it had bought from other vendors.

Both Flixster and Charter say they were unaware of Epic's activities and have since removed all Epic technology from their sites. Charter did the same last year with a different vendor doing history stealing on a smaller scale.

Gathering information about Web-browsing history can offer valuable clues about people's interests, concerns or household finances. Someone researching a disease online, for example, might be thought to have the illness, or at least to be worried about it.

The potential for privacy legislation in Washington has driven the online-ad industry to establish its own rules, which it says are designed to alert computer users of tracking and offer them ways to limit the use of such data by advertisers.

Under the self-imposed guidelines, collecting health and financial data about individuals is permissible as long as the data don't contain financial-account numbers, Social Security numbers, pharmaceutical prescriptions or medical records. But using techniques such as history stealing and supercookies "to negate consumer choices" about privacy violates the guidelines, says Lee Peeler, executive vice president of the Council of Better Business Bureaus, one of several groups enforcing the rules.

Until now, the council "has been trying to push companies into the program, not kick them out," Mr. Peeler says. "You can expect to see more formal public enforcement soon."

Last year, the online-ad industry launched a program to label ads that are sent to computer users based on tracking data. The goal is to provide users a place to click in the ad itself that would let them opt out of receiving such targeted ads. (It doesn't turn off tracking altogether.) The program has been slow to catch on, new findings indicate.

The industry has estimated that nearly 80% of online display ads are based on tracking data. Mr. Mayer, along with researchers Jovanni Hernandez and Akshay Jagadeesh of Stanford's Computer Science Security Lab, found that only 9% of the ads they examined on the 500 most popular websites—62 out of 627 ads—contained the label. They looked at standard-size display ads placed by third parties between Aug. 4 and 11.

The industry says self-regulation is working. Peter Kosmala, managing director of the Digital Advertising Alliance, says the labeling program has made "tremendous progress."

Mr. Mayer discovered that several Microsoft-owned websites, including MSN.com and Microsoft.com, were using supercookies.

Supercookies are stored in different places than regular cookies, such as within the Web browser's "cache" of previously visited websites, which is where the Microsoft ones were located. Privacy-conscious users who know how to find and delete regular cookies might have trouble locating supercookies.

Mr. Mayer also found supercookies on Microsoft's advertising network, which places ads for other companies across the Internet. As a result, people could have had the supercookie installed on their machines without visiting Microsoft websites directly. Even if they deleted regular cookies, information about their Web-browsing could have been retained by Microsoft.

Microsoft's Mr. Hintze said that the company removed the code after being contacted by Mr. Mayer, and that Microsoft is still trying to figure out why the code was created. A spokeswoman said the data gathered by the supercookie were used only by Microsoft and weren't shared with outside companies.

Separately last month, researchers at the University of California at Berkeley, led by law professor Chris Hoofnagle, found supercookie techniques used by dozens of sites. One of them, Hulu, was storing tracking coding in files related to Adobe Systems Inc.'s widely used Flash software, which enables many of the videos found online, the researchers said in a report. Hulu is owned by NBC Universal, Walt Disney Co. and News Corp., owner of The Wall Street Journal.

Hulu was one of several companies that entered into a $2.4 million class-action settlement last year related to the use of Flash cookies to circumvent users who tried to delete their regular cookies.

The Berkeley researchers also found that Hulu's website contained code from Kissmetrics, a company that analyzes website-traffic data. Kissmetrics was inserting supercookies into users' browser caches and into files associated with the latest version of the standard programming language used to build Web pages, known as HTML5.

In a blog post after the report was released, Kissmetrics said it would use only regular cookies for future tracking. The company didn't return calls seeking comment.

Goodbye summer :-/

Keeping Great People with Three Kinds of Mentors

Who is your mentor? The follow article from HBR is a terrific reminder that mentorship is alive, well and necessary...

To attract and retain great people, several things need to coalesce. From the extrinsic reward of a salary to the more nuanced (and more important) intrinsic reward of people feeling that they have a meaningful role, it requires thought and a proactive approach to keep talent once you've got it.

One of the most critical elements in retaining great people is effective mentoring. But what does that really mean? The word "mentoring" is too general to capture the specifics of what people need through the different stages of a career. It is akin to saying that people need to be educated — and then implementing a teaching curriculum that is the same every year for everyone. Like education, mentorship requires different things at different stages, including different types of skills and advice, and different types of teachers and learning styles.

1. Buddy / Peer Mentoring

2. Career Mentoring

3. Life Mentoring

1. Buddy / Peer Mentors This is the starting point for mentoring, where it is less about mentorship and more about an apprenticeship. During the entry-level, early stages of a career, or when "on-boarding" to a new job, what really benefits someone is a "buddy" or peer-based mentor who can help one get up the learning curve faster. This type of peer mentor is focused on helping with specific skills and basic organizational practices of "this is how it is done here." This can happen to some extent informally, through social and professional networks online and offline. But assigning a buddy day one on someone's new job is a great "I care" practice. This is a high frequency mentor who interacts as needed in those first couple of years.

2. Career Mentors After the initial period at a workplace, employees need to have someone who is senior to them to serve as a career advisor and internal advocate. A career mentor should help reinforce how the mentee's job contributions fit into the bigger picture and purpose of the firm. People don't contextualize the purpose of one's career enough. When people feel that they understand their current role, its impact and where it can take them next in a company, it leads to higher levels of satisfaction and motivation. Note that a career mentor is not necessarily the manager who may be doing the mentee's performance evaluation reviews. In fact, it may be better if it is not. Think of your most respected managers and rising stars — your real people people — who enjoy and are willing to spend the extra time to provide counsel as go to career mentors. In a career mentor, an employee should feel that they have an "I've got your back" advocate and advisor inside the company. Career mentors should look to meet with their mentee semi-annually or quarterly.3. Life Mentors These may be the most important mentors to have. They can be people inside the mentee's company, but also outside. As people reach mid- and senior stages of their careers, they need to have someone in whom they can confide without feeling that there is any bias. This is someone who can be a periodic sounding board when one is faced with a difficult career challenge, or when is considering changing jobs. A company's alumni network is often a good place for life mentors, but employees should be encouraged to find these mentors outside of a firm's affiliation as well. The senior folks at a company should make it a part of their objectives to be a life mentor to rising stars, and to put younger associates in situations where they can meet some of the firm's institutional relationship network. Most of the better strategic consulting firms do a decent job of this as they make regular efforts to expose current employees to their firm's alumni and other relations. Retention would likely go up in many companies if employers demonstrated that they openly and fearlessly tried to do what is best for the employee — that they saw their employees as being as important as their customers. Companies should want to do what is best for their employees even if that means helping look for a job elsewhere. Life mentors do not supplant career mentors or peer mentors (and in some cases may be one and the same), but they are there to impart career wisdom. And whatever your employer does, you should look for at least one life mentor (if not a small council of them), and ideally set an annual dinner meeting with her, him, or them.

Beyond this mentoring taxonomy, there are many other aspects of mentoring, people development, and retention that could fill a book. In future blog posts, I'll touch on other key people themes and strategies. But start by making mentoring a priority in your company culture, and consider this simple three-part structure to help match the right mentorship to the right stage of professional development.

Anthony Tjan is CEO, Managing Partner and Founder of the venture capital firm Cue Ball. An entrepreneur, investor, and senior advisor, Tjan has become a recognized business builder.

ANTHONY TJAN

"Groupon Doomed by Too Much of a Good Thing" via @hbr

"Alright, you caught us. We're actually not making any money. In fact, we are really losing a lot of money."

This is the essence of Groupon's declaration last week that it will remove the controversial accounting metric calledAdjusted Consolidated Segment Operating Income (ACSOI) from its financial statements. ACSOI essentially measures Groupon's profits before subtracting its subscriber-acquisition costs and stock option-based compensation. The metric was an attempt to put a thin veneer of respectability on what are extremely disconcerting profitability numbers for the company. In the first quarter of 2011, Groupon posted a net loss of $113.9 million. Yet, the company reported ASCOI of positive $80.1 million. In most recent quarter, Groupon's losses continued to mount as it begrudgingly abandoned the ACSOI metric amidst criticism and incredulity from the SEC.

But what is most interesting about its emphasis on the ACSOI metric is that, deep down, Groupon knows what we all know: good investments are profitable investments. It was simply not enough for the firm to report earnings and explain that it was investing for growth. Rather, Groupon felt the need to include a metric of profitability, no matter how contrived, that was actually positive. Clayton Christensen would agree with the intuition that Groupon displays but ignores: businesses should become profitable before they become big. The best way to manage a fledgling business is for managers to be impatient for profit but patient for growth. Such a strategy limits an early venture's funding in order to force the business to develop a profitable business model and then invests heavily in growth once such a model is identified — Christensen terms such investments"good money" for incubating growth businesses and extols the strategy for three reasons. Groupon's fundamental problem is that it has not yet discovered a viable business model.The company asserts that it will be profitable once it reaches scale but there is little reason to believe this. The financial results of Groupon's traditional business continue to deteriorate, especially in mature markets, and new ventures such as Groupon Now also have failed to drive profits. And unlike the very few successful companies that scaled before they were profitable (think Facebook or Amazon), Groupon's business model does not benefit from significant network effects. The company's product is not more valuable to users as more people adopt the platform. If anything, the fact that Groupon is witnessing decreasing revenue per merchant and fewer Groupon purchases per subscriber in its maturing markets suggests that growth may actually decrease Groupon's value to its customers. Yet, Groupon maintains a blind faith that growth will be its salvation. As Pets.com learned in the last bubble, such a strategy works just fine until you run out of other people's money to spend on growth. The real cause of Groupon's problem is that it had too much of a good thing. With over $1 billion of venture capital money to invest in growth, what manager has time to worry about profitability? Groupon's "bad money" — investments that were patient for profit but impatient for growth — did not instill the discipline needed to enable the company to emerge as a successful standalone venture. Now, the venture capital markets cannot supply more capital and the company must depend on the IPO market to finance its money-losing operations. Eventually, investors will be unable to sell their shares to a greater fool and Groupon will be added to the list of companies that had immense potential but died because they did not find a successful profit formula in time. The story would be much different if Groupon did not have nearly unlimited access to funding so early in its corporate life. A successful financing strategy would have provided Groupon with incremental investments to enable the development of a profitable business model around a product that had obvious appeal to customers and merchants. In such a world, Groupon would have stuck to its home market of Chicago until it developed a business model that was profitable at scale in one market. Armed with a viable profit formula, Groupon could have scaled aggressively — confident that much larger profits awaited it. But it is now too late. Groupon needs another $750 million to keep the lights on and to keep growing while it prays for profitability that will perpetually lay just one funding round away. Groupon's venture investors and executives need a way to cash out before everyone realizes that the emperor has no clothes. I will probably buy a Groupon every now and again — I have no problem letting investors finance my cheap consumption. But as far as an investment goes, Groupon is looking about as profitable as giving away your merchandise for 90% off.